Thank you for visiting this website. You may be visiting this site as a family member of a veteran, a Vietnam veteran or as member of the public. I appreciate your interest in reading these stories. These stories take the third person point of view, thus the title “A Vietnam Soldiers Perspective”.

The American role in the Vietnam War lasted from 1955 to 1975. Over the years, more information of the Vietnam war has become available, and the general public has been able to learn more about this war. Perhaps one watershed moment for this information was the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. The Memorial Wall was a catalyst that increased the public awareness of that war. The Wall and other high-profile books and movies made a difference among Vietnam veterans and their willingness to talk about that war.

The public has come to appreciate the contributions made by veterans of the Vietnam war. I hope these stories of my Vietnam experience will sharpen and heighten your appreciation for the contributions made by 2.7 million veterans who served in Vietnam and the 58,467 who served in Vietnam and made the ultimate sacrifice. I welcome your contributions of content and your response to these stories.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Norm Te Slaa

The American role in the Vietnam War lasted from 1955 to 1975. Over the years, more information of the Vietnam war has become available, and the general public has been able to learn more about this war. Perhaps one watershed moment for this information was the construction of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in Washington, D.C. The Memorial Wall was a catalyst that increased the public awareness of that war. The Wall and other high-profile books and movies made a difference among Vietnam veterans and their willingness to talk about that war.

The public has come to appreciate the contributions made by veterans of the Vietnam war. I hope these stories of my Vietnam experience will sharpen and heighten your appreciation for the contributions made by 2.7 million veterans who served in Vietnam and the 58,467 who served in Vietnam and made the ultimate sacrifice. I welcome your contributions of content and your response to these stories.

Thank you.

Sincerely,

Norm Te Slaa

Story Index:

6. A Disease of Undetermined Origin

5. The Long Silence

4. Stop it! Stop it! Stop it!

3. Squeak

2. Road to Nowhere

1. Prologue to Vietnam

A. Map of Southeast Asia during Vietnam War

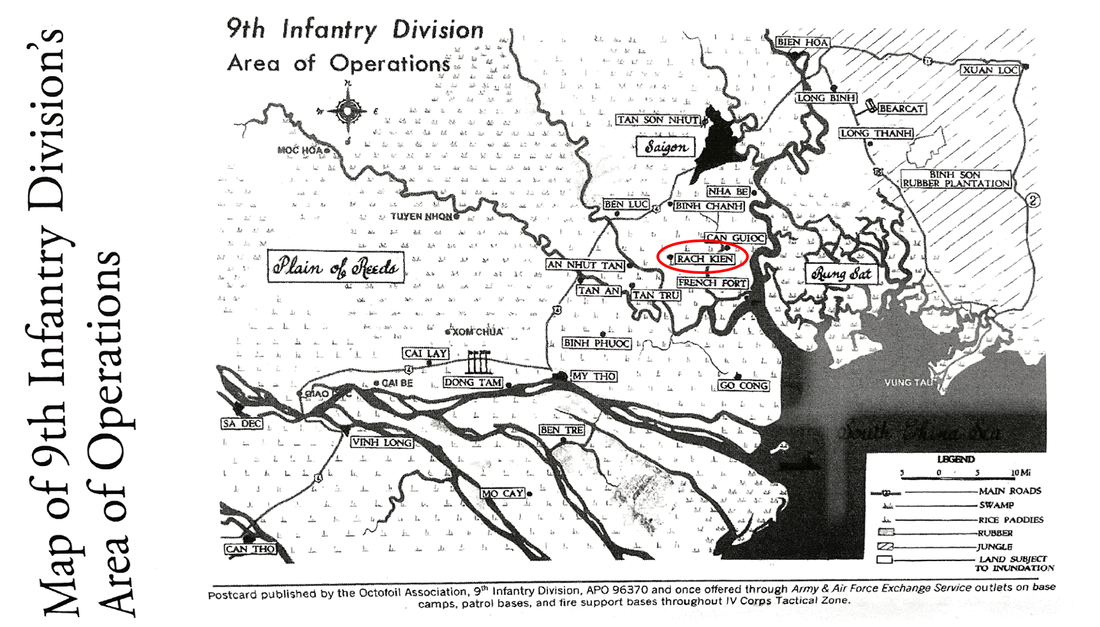

B. 9th Infantry Division Area of Operations with Rach Kien

6. A Disease of Undetermined Origin

“Well, Spec. 4, you have a disease of undetermined origin.” It was an orderly at the army hospital in Saigon talking to the Spec. 4 soldier, newly awakened from unconsciousness.

“What do you mean, a disease of undetermined origin?” the patient asked warily.

“The doctor was unable to precisely diagnose the problem. The symptoms are similar to malaria, but they were not exactly like malaria. So in lieu of labeling the sickness as malaria, the doctor labelled it as a ‘disease of undetermined origin’.” explained the orderly.

The soldier slowly gathered his wits. He tried to reason out such a verdict. He could believe a diagnosis of malaria…but a disease of undetermined origin? He knew malaria was a common sickness in Vietnam. He had been very conscientious about putting two quinine tablets into his canteen drinking water, a requirement of all soldiers in the field.

He knew it was not a contagion like some GIs who experienced malaria-type symptoms. The orderly explained that there were several malaria-like diseases common in Vietnam among soldiers.

What was the orderly talking about that?

Was he talking about a sexually transmitted disease? Was he avoiding talking to him about subjects not normally discussed in polite company? Was he trying to save him from embarrassment…but he had nothing to be embarrassed about. There was no possibility he could have contracted ‘the clap’ as the GI’s referred to that class of diseases.

So, what could it be?

His mind began to review the mission of the past three or four days. He recalled Charlie Company had been in the field for several days. Their canteens had been empty for some time. Mosquitoes and blood suckers were plentiful but clean water was not. The company had been in and near several villages. He recalled he had bought sodas from a local Vietnamese mamasan.

He knew the company hadn’t been resupplied by helicopter, since the distinctive thump-thump of the helicopter blades, and the noise of the engine could alert the local VC or NVA to our presence in the area. He remembered waking up the morning of the third day, after laying all night in a defensive position on the inside of rice paddy dike. The rice paddy had been dry and the soil was hard as concrete, creased with large cracks. Their fixed defensive positions had allowed very little movement throughout the night. His body was stiff and sore. The platoon was exhausted from the daily strain of patrols and guard duty that everybody had to pull more than once during the night. There was no combat activity so far during the mission, but the platoons were edgy.

The platoons began to break camp. He noticed there was no energy in his body to prepare for the next mission. He could not stand up. Platoon SSGT Kay observed his slowness, his incoherent speech and ashen, pasty-white face. He called Doc Martin, the medic, who came and took the soldier’s temperature. Doc Martin conferred with SSGT Kay and immediately called for a dust-off [1] for this nearly, unresponsive G.I. now going in and out of consciousness. Within minutes, there was a call to headquarters to medivac this soldier out of the field.

For evacuees from the field, there were no ‘good-luck’ or ‘good-byes’ from the platoon. He was just another soldier being taken out of the field. Some members of the platoon often expressed relief for an evacuated soldier without life-threatening injuries who was dusted off, secretly wishing it would have been one of them. They realized that now that evacuee might have a chance of escaping from combat with their lives and limbs intact.

After fifteen or twenty minutes the medivac helicopter arrived. The soldier came in and out of consciousness while his body and hands were being strapped to a stretcher. The basket-like stretcher was then tied to the skids on the outside of the helicopter. He looked up to see the underside of M60 machine gun muzzle above his feet.

He felt no fear or anxiety of being strapped to the outside of the helicopter. It was normal on eagle flights [2] for platoon members to be sitting two or three abreast at the open door with their feet resting on the helicopter skids. Such a transport arrangement still left room for the M60 machine gunners on each side of the helicopter to maneuver and three riflemen on each side of helicopter to lay down a field of fire when landing in a hot LZ [3] .

He lost consciousness before the helicopter became airborne, and he didn’t regain it until the helicopter landed at Tan An, a field hospital in their area of operation. The medics took off his clothes and boots and stripped him naked. He was placed on a gurney and transported into the field hospital.

Inside the field hospital, and barely inside the main ward, was a large steel tank the size of a bathtub. The tank appeared to be filled with water. But water it was not! It was filled with ice-cold alcohol.

The orderlies slowly lowered him into the tank and submerged him from his toes to his chin until his entire body was enveloped by the icy alcohol, only his mouth escaped the shock.

His reintroduction to reality was immediate. He was shocked into temporary consciousness. He had no recall how long he stayed in this liquid deep freeze but probably only a matter of minutes. Whatever the time he spent in the alcohol bath, it may have been at least partially successful in getting his fever down from 107 degrees. He lost consciousness again after being taken out of the alcohol. He had no recollection of what happened after the Tan An alcohol bath.

He awoke on some future day, perhaps a day or two, in the Army hospital in Saigon. At the foot of his bed was the battalion commander of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Infantry. (Photo in hospital) He was talking to the Spec. 4. It was his practice to visit all the hospitalized soldiers in his battalion.

Wearily, the soldier greeted his commander. [4] He realized he was in a hospital ward surrounded by other sick or wounded GIs. The commander spent a few minutes with him and then moved on to the next bed in the ward.

The Spec. 4 had no recollection of what was said between him and his battalion commander. But he did recall being grateful and impressed that he took the time to express his concern.

After four or five days in the Saigon Army hospital, he was released to return to his unit in Rach Kien. They issued him new combat fatigues and left it up to him to find his way back to the base camp. He caught a ride on the back of a deuce-and-a-half supply truck heading to his firebase, not unlike his first ride months before from Bien Hoa to Rach Kien.

He had no special memories of his return to base camp. He was just a guy who was being sent back to his unit to resume his duties as a soldier. There was no backslapping, no exuberant welcome-back greetings from his squad or platoon, just business as usual. Within two days, he was back in the field carrying radio for the lieutenant.

However, there is a bit of humor within this story.

Humor may be disguised in the form of mistaken identity. Mistaken, in the sense that if the disease was not malaria, then what was it? The answers are limited but the interpretations and assumptions could be many. The real cause of his sickness and the unanswered questions posed from his fellow GIs, and later his family and friends, he intentionally left open the answer for all manner of interpretations.

It became a source of speculation. Over the years, he watched the bemused, but doubtful responses of his listeners as he told the story. He noticed their sly smiles, their imperceptively-raised eyebrows, their suspicious looks, their winks, and retorts like, sure, who are you kidding?

A disease of undetermined origin? Really?

Footnotes:

[1] A dust-off was a helicopter who removed sick or injured soldiers and ferried to them to a field hospital.

[2] An eagle flight by helicopter quickly brought troops to a site for a potential engagement of the enemy

[3] A hot LZ was when the helicopters and troops landed under enemy fire.

[4] Photo taken of soldier by the battalion commander’s staff with the soldier’s commanding officer.

CONTRIBUTORS: Editor, Kim Van Es. Proofreader, Cathy Te Slaa, Web Master, Caesar Orosco

“What do you mean, a disease of undetermined origin?” the patient asked warily.

“The doctor was unable to precisely diagnose the problem. The symptoms are similar to malaria, but they were not exactly like malaria. So in lieu of labeling the sickness as malaria, the doctor labelled it as a ‘disease of undetermined origin’.” explained the orderly.

The soldier slowly gathered his wits. He tried to reason out such a verdict. He could believe a diagnosis of malaria…but a disease of undetermined origin? He knew malaria was a common sickness in Vietnam. He had been very conscientious about putting two quinine tablets into his canteen drinking water, a requirement of all soldiers in the field.

He knew it was not a contagion like some GIs who experienced malaria-type symptoms. The orderly explained that there were several malaria-like diseases common in Vietnam among soldiers.

What was the orderly talking about that?

Was he talking about a sexually transmitted disease? Was he avoiding talking to him about subjects not normally discussed in polite company? Was he trying to save him from embarrassment…but he had nothing to be embarrassed about. There was no possibility he could have contracted ‘the clap’ as the GI’s referred to that class of diseases.

So, what could it be?

His mind began to review the mission of the past three or four days. He recalled Charlie Company had been in the field for several days. Their canteens had been empty for some time. Mosquitoes and blood suckers were plentiful but clean water was not. The company had been in and near several villages. He recalled he had bought sodas from a local Vietnamese mamasan.

He knew the company hadn’t been resupplied by helicopter, since the distinctive thump-thump of the helicopter blades, and the noise of the engine could alert the local VC or NVA to our presence in the area. He remembered waking up the morning of the third day, after laying all night in a defensive position on the inside of rice paddy dike. The rice paddy had been dry and the soil was hard as concrete, creased with large cracks. Their fixed defensive positions had allowed very little movement throughout the night. His body was stiff and sore. The platoon was exhausted from the daily strain of patrols and guard duty that everybody had to pull more than once during the night. There was no combat activity so far during the mission, but the platoons were edgy.

The platoons began to break camp. He noticed there was no energy in his body to prepare for the next mission. He could not stand up. Platoon SSGT Kay observed his slowness, his incoherent speech and ashen, pasty-white face. He called Doc Martin, the medic, who came and took the soldier’s temperature. Doc Martin conferred with SSGT Kay and immediately called for a dust-off [1] for this nearly, unresponsive G.I. now going in and out of consciousness. Within minutes, there was a call to headquarters to medivac this soldier out of the field.

For evacuees from the field, there were no ‘good-luck’ or ‘good-byes’ from the platoon. He was just another soldier being taken out of the field. Some members of the platoon often expressed relief for an evacuated soldier without life-threatening injuries who was dusted off, secretly wishing it would have been one of them. They realized that now that evacuee might have a chance of escaping from combat with their lives and limbs intact.

After fifteen or twenty minutes the medivac helicopter arrived. The soldier came in and out of consciousness while his body and hands were being strapped to a stretcher. The basket-like stretcher was then tied to the skids on the outside of the helicopter. He looked up to see the underside of M60 machine gun muzzle above his feet.

He felt no fear or anxiety of being strapped to the outside of the helicopter. It was normal on eagle flights [2] for platoon members to be sitting two or three abreast at the open door with their feet resting on the helicopter skids. Such a transport arrangement still left room for the M60 machine gunners on each side of the helicopter to maneuver and three riflemen on each side of helicopter to lay down a field of fire when landing in a hot LZ [3] .

He lost consciousness before the helicopter became airborne, and he didn’t regain it until the helicopter landed at Tan An, a field hospital in their area of operation. The medics took off his clothes and boots and stripped him naked. He was placed on a gurney and transported into the field hospital.

Inside the field hospital, and barely inside the main ward, was a large steel tank the size of a bathtub. The tank appeared to be filled with water. But water it was not! It was filled with ice-cold alcohol.

The orderlies slowly lowered him into the tank and submerged him from his toes to his chin until his entire body was enveloped by the icy alcohol, only his mouth escaped the shock.

His reintroduction to reality was immediate. He was shocked into temporary consciousness. He had no recall how long he stayed in this liquid deep freeze but probably only a matter of minutes. Whatever the time he spent in the alcohol bath, it may have been at least partially successful in getting his fever down from 107 degrees. He lost consciousness again after being taken out of the alcohol. He had no recollection of what happened after the Tan An alcohol bath.

He awoke on some future day, perhaps a day or two, in the Army hospital in Saigon. At the foot of his bed was the battalion commander of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Infantry. (Photo in hospital) He was talking to the Spec. 4. It was his practice to visit all the hospitalized soldiers in his battalion.

Wearily, the soldier greeted his commander. [4] He realized he was in a hospital ward surrounded by other sick or wounded GIs. The commander spent a few minutes with him and then moved on to the next bed in the ward.

The Spec. 4 had no recollection of what was said between him and his battalion commander. But he did recall being grateful and impressed that he took the time to express his concern.

After four or five days in the Saigon Army hospital, he was released to return to his unit in Rach Kien. They issued him new combat fatigues and left it up to him to find his way back to the base camp. He caught a ride on the back of a deuce-and-a-half supply truck heading to his firebase, not unlike his first ride months before from Bien Hoa to Rach Kien.

He had no special memories of his return to base camp. He was just a guy who was being sent back to his unit to resume his duties as a soldier. There was no backslapping, no exuberant welcome-back greetings from his squad or platoon, just business as usual. Within two days, he was back in the field carrying radio for the lieutenant.

However, there is a bit of humor within this story.

Humor may be disguised in the form of mistaken identity. Mistaken, in the sense that if the disease was not malaria, then what was it? The answers are limited but the interpretations and assumptions could be many. The real cause of his sickness and the unanswered questions posed from his fellow GIs, and later his family and friends, he intentionally left open the answer for all manner of interpretations.

It became a source of speculation. Over the years, he watched the bemused, but doubtful responses of his listeners as he told the story. He noticed their sly smiles, their imperceptively-raised eyebrows, their suspicious looks, their winks, and retorts like, sure, who are you kidding?

A disease of undetermined origin? Really?

Footnotes:

[1] A dust-off was a helicopter who removed sick or injured soldiers and ferried to them to a field hospital.

[2] An eagle flight by helicopter quickly brought troops to a site for a potential engagement of the enemy

[3] A hot LZ was when the helicopters and troops landed under enemy fire.

[4] Photo taken of soldier by the battalion commander’s staff with the soldier’s commanding officer.

CONTRIBUTORS: Editor, Kim Van Es. Proofreader, Cathy Te Slaa, Web Master, Caesar Orosco

5. The Long Silence

I. The Long Silence

“Why should I remember what took many years to forget?” asked a Vietnam veteran.

For nearly thirty-five years, I rarely spoke about the Vietnam War with anyone. I found no compelling reason to talk about it. Exceptions to that silence were few—perhaps to answer a question from a friend or family member, or during an infrequent conversation about Vietnam with my wife. If I had to talk about it, more often than not, I would trivialize the experience. Bad times were really not that bad, or talking only about the good, the funny, or not-so-difficult times.

But there was no way I could control life events, and sometimes something happened that forced me to a recall an experience from Vietnam. These penetrations past my mental blockages came at surprising, unexpected moments, connecting me in some way to my time in the war—a hitchhiker trying to catch a ride on an approach to a highway, seeing a serviceman in uniform, or hearing the whoop-whoop of an Army helicopter overhead.

After returning from Vietnam, I wanted to move on with my life. My mind and my lips snapped shut on Vietnam. I had many reasons constricting my lips and closing my mind.

Most returning Vietnam veterans quickly learned that there was divided public opinion about the war. Even those veterans who were willing to talk about their experiences were reticent to breach the topic in conversation.

We were not welcomed as returning patriots or conquering heroes to America. A large segment of the population greeted us with silence, a deep distrust, and even disdain. As one Vietnam veteran put it, “The road home from war and the quiet that followed was sobering.” We were even shunned by veterans of prior wars. For many years after the war ended in 1975, the American Legion would not accept Vietnam veterans into their membership. They told us that Vietnam was never a real war and, by inference, we were not real soldiers.

Few people were interested in learning more or opening their perceptions of Vietnam. In that silence, my own recollections of Vietnam faded. It seemed easy to bury my recollections of the war into a vault to be forgotten and never opened again. My amnesia was self-inflicted.

But my silence around Vietnam was also self-preservation. It avoided questions like, “Did you ever kill anybody?” or “What was it like to shoot somebody?” “What was the worst thing that happened to you in Vietnam?”

I presumed that the people asking those questions had little interest in hearing the more important stories behind the headlines—the heartache of losing a brother to injury or death, the anger of obeying insane orders from a superior officer, the persistent feeling of loneliness and isolation. How does one explain the experience of living on an “island of war?”

To avoid the possibility of such conversations, I avoided the subject altogether. However, I’ve since learned from talking with fellow Vietnam veterans, that they too carried that same sort of reticence to relive their experiences. They—like me—were unsure whether they would be able to control themselves if those memories were awakened.

Perhaps there is a more truthful, personal answer to the question: Why was I so quiet about Vietnam for so long? Was I was afraid of awakening that sleeping monster along with its entourage of protégé monsters? Did I fear that retelling, rehashing, or rehearing about the Vietnam war would stir up emotions so overwhelming that I would not be able to control myself, and my emotions in turn would take control of me? I was paralyzed by the possibility that opening this Pandora’s box of the confusion and chaos of Vietnam would consume my existence.

I had no known physical wounds from Vietnam—unlike thousands of others who still suffer those consequences to this day. For them, there are daily conscious and subconscious reminders of Vietnam. The ever-present physical damage and emotional wounds left some brothers with thoughts of suicide. The scars incurred in Vietnam did not necessarily fade away.

I knew of other veterans whose lives had been so shattered by Vietnam that they had disintegrated into poorly functioning human beings. What if I would be no different? I had not yet been tested to know how I might react if I broke the long silence. I had consciously chosen to maintain my silence, that is, until my phone rang.

II. The Long Silence Lifts

The caller asked, “Is this the Norm Te Slaa who served with the 5th of the 60th Infantry Division of the 9th Division in Rach Kien, Vietnam?”

I fell silent for moment. After all these years, how could a voice suddenly emerge, seemingly out of nowhere, and ask about Vietnam? Was this a crank call or a sales pitch?

He sensed my reticence and quickly introduced himself. “Norm, this is Tony. We served together with the 5th of the 60th in Rach Kien.”

I quickly searched my dusty memories for his name. Yes, I remembered a Tony, but I barely knew him in Vietnam. That was not unusual, as we usually referred to each other by last names or some nickname the men had conjured up.

I vaguely recalled him. There was a day during my third month in the field when he had been walking point [1] and was injured by a booby trap. He was shipped back to the United States for hospitalization, recovery, and a purple heart. I had not heard from him or about him since then.

He continued, “Norm, have you heard that the 5th of the 60th has been having battalion reunions every other year for the last several years?” I hesitatingly answered that no, I had not heard about them. My conversation with Tony moved slowly, mainly because of my delayed responses to his comments and questions. I had a hard time understanding why he was calling to invite me to a reunion now. I was not prepared for such a call. In so many ways, it was the furthest thing from my mind.

Tony then invited me to attend the battalion reunion coming up in St. Louis in the spring of that year. As we talked, he told me more about the four previous reunions, and he mentioned that the special guest speaker at the next reunion would be one of the generals of our battalion during 1969, General Franks. His name also barely registered in my memory.

I was wary of attending and my doubts continued. After all, I could not remember many names from 1968 to 1969, only four or five came to mind, and these blank spaces in my memory concerned me. If I did attend, how could I even carry on a good conversation with the others? I was even unsure of my assigned platoon and squad number. And yet, my memory of certain events during that year could still be played back in technicolor.

Did I want to continue this conversation? If I did continue, would my confusion and feelings of chaos around my memories of Vietnam come crashing in, destroying my quiet life and successful career?

But slowly, I relaxed, and my reticence eased. I shifted from shielded to inquisitive, and I began to ask questions. The conversation began to feel more normal, even as my doubts about attending this reunion continued to bubble up.

My first impulse was to say no to the invitation. But hesitantly, I said I would think about it. I needed time to deliberate whether I wanted to let Vietnam back into my life. Sometime later, I called Tony back and told him, yes, I would come. But my doubts and apprehensions lingered.

Yet, I knew I needed to give my long silence a trial termination.

III. The Long Silence Ends

I attended my first reunion in the spring of 2012. Remembering Vietnam was initially very difficult; I could only recall a few names and places associated with Vietnam. But beginning with my first reunion, connections with my Vietnam past began to emerge.

I found myself among veterans who were not only willing to talk about Vietnam—they wanted to. We felt an immediate understanding and comradery among us. It was my first recollection of another Vietnam veteran calling me ‘brother’.

I soon learned that the 5th of the 60th reunion was an emotionally safe place. For many, the reunion was an act of self-preservation—finding a space where others understood them, also carrying similar questions, doubts, and apprehensions. At the reunion, veterans were ready to talk about Vietnam.

All around us were reminders of the physical damage. Some brothers lived every day with the tangible legacy of their Vietnam service. The manifestations of psychological damage, however, was less noticeable, at least initially.

I was relieved that others were also surprised at how little they recalled about details of daily existence in Vietnam. They, too, were hesitant to relive their experiences and had participated in their own ‘long silence.’ Fellow veterans said things like, “I don’t remember that.” or “What was his name?” or “Did we do that?”

I also learned that every Vietnam veteran had experienced a different version of Vietnam. Understanding these differences of experiences began with a soldier’s Military Occupational Service—their MOS. [2] I had been ground infantry, the MOS designation for which was 11B.

Approximately 2.7 million American men and women served in the Vietnam War, and for each 11B soldier in the field, it took eight or nine soldiers in the rear to support them. That breadth of different duties help account for the wide spectrum of interpretations of the Vietnam soldier’s experience.

Some of those 11B soldiers who had witnessed and participated in combat and bloodshed were left with emotional wounds. They returned home only to be swallowed up in their own quiet, psychological quagmire that filled their lives with trauma. And for the soldiers returning with lifelong physical damage, there was no escape from the daily reminder of their Vietnam service.

Few soldiers ever aired their emotional wounds. Some waited for years before allowing their Vietnam memories back into their thoughts. But some veterans seized the opportunity to unload their burdens at battalion reunions.

At a reunion of a battalion of grunts, among fellow, trusted brothers, veterans did not need to be as cautious as they talked about their memories and traumas. I saw this at my first battalion reunion. One brother’s expression of his trauma still replays vividly in my memory.

On the first day of my first reunion, Tony and I were walking down the hotel hallway, passing rooms with different gatherings of brothers, usually grouped by platoon. These gatherings were called ‘talk backs’ when brothers could meet with their squad or platoon and just talk about what was on their mind or reminisce together. Each room’s door was open, welcoming any latecomers.

We were talking as we passed by the third door when Tony suddenly grabbed my arm, stopping us. He shushed me and said, “Please be quiet! One of the guys is spilling his guts.”

Silently from the hallway we observed a brother sharing his trauma with his platoon. He was sobbing and in obvious distress. Neither of us heard what he was saying, but we could feel that it was an emotional avalanche. We were witnessing decades of emotional pressure being released.

For me, not being in the room, I feared we were betraying the confidence of our brother inside the room. After all, we were eavesdropping at a moment when he was finally able to bare his soul among his comrades and confidants, each of whom listened with understanding, compassion, and without judgement. Did I have the right to observe such a personal expression without his permission? The sight brought tears to my eyes. I could only imagine his sadness, his long-endured pain, and the endless sleepless nights he had suffered.

Tony and I moved on down the hallway, hoping the dark cloud enveloping this brother might now lift. To this day, when I think of him—and so many others—carrying such suffering, I find it hard to hold back my own tears.

This moment from my first reunion—and many more like it—is a testament to the fact that the emotional scars from Vietnam don’t necessarily melt away. The wounds of war can mark us indefinitely. These daily reminders of the Vietnam trauma—both conscious and subconscious—pick at the scabs of our memories.

At the age of twenty-three, I was one of the older grunts in my platoon. My maturity may have been one of the reasons why I sustained fewer traumas than some of my teenaged platoon brothers. The other reason being that my main field time job was as a radio operator, in addition to being a rifleman.

My main job was to carry the radio for the platoon leader, usually a second lieutenant. The two of us were usually in the middle of a line formation. My job was to have the field radio immediately available for the platoon leader so he could maintain contact with other platoons of the company or headquarters company.

Because of my radio responsibilities, I was also never tasked to carry an injured or deceased brother to a medivac helicopter. I never had to bind up the wounds of a booby trap or gunshot victim. That’s not to say I didn’t see them happen. I did. But for the most part, I was spared some of the severity of that trauma. Others who carried our brothers and bound their physical wounds, went on to carry their own emotional wounds throughout their lives. I am eternally grateful to my brothers, and especially our medics, who bore the responsibility of taking care of our injured and fallen soldiers.

Now, many years later, I still need to come to terms with certain subjects. A tear might unexpectedly appear when certain subjects come up. When that happens, my face freezes, my lips purse, and my mouth closes tightly, I swallow hard as I try to hold my emotions captive and avoid embarrassment.

After more than a decade of unpeeling the protective layers of silence, I began to see how close to the surface my own emotions actually are. I won’t go into detail here, but two very public events happened relatively recently that poked that slumbering monster within me. During each, I was asked to recall an experience, and doing so forced me to confront the fact that the pain of some events was still fresh within me.

I don’t regret what I did in Vietnam. I did as I was told. I also prayed a lot. I smoked packs of cigarettes every day, and I tried to stay close to my moral anchors. I did what I could to protect my brothers, and I took control of situations when I could to shield others from further harm. I am not ashamed of anything I did during my time in Vietnam. This alone helps me sleep peacefully.

So, why do I now write about something that happened so long ago?

First, I write because the remembrance of the Vietnam War is fast fading from the American conversation. Today, the people who might understand or even care about a living soldier’s story of his Vietnam War, and the people who walked those roads and rice paddies, manned and survived the ambushes, rode innumerable eagle flights, and walked miles and miles of search and destroy missions, are dying away. Soon, the Vietnam War will be only a footnote in history.

Second, I write because I cannot forget or ignore the sacrifices made by the 56,478 soldiers who gave their lives, and the over 300,000 soldiers physically injured—and even more emotionally wounded—in service of our nation’s call to duty. How can I remain silent in the face of their absent limbs, fractured minds, and muffled voices from the grave? Staying silent only increases the injustice of their sacrifice.

Third, I write to remind the public that there are people living among us who agreed to risk their lives for our country. Why should I not do what I can to honor their commitment to serve and face the danger of dying in war?

And finally, I write because many veterans have come to understand that none of us can keep our Vietnam combat experiences silent and locked away. If we ignore what happened in Vietnam, we do so at our own peril.

Until recently, I felt that wearing a Vietnam veteran cap was a distraction. But I no longer feel that way. Quite the opposite. Now, wearing this cap reminds me and others who see the cap’s insignia that there was such a momentous American event called the Vietnam War. It involved not only the people who served in the military. It touched and affected all of America. It tore our society apart.

Many Americans and Vietnamese died. Many more were injured. Some recovered from their injuries, but many did not. Wearing a reminder of the Vietnam War speaks to the sacrifices and the price that thousands of American soldiers paid, and continue to pay today. And we speak to break the long silence that holds us captive.

Why shouldn’t we remember what it took many years to forget?

Footnotes:

[1] A soldier walking point was the first in a line of soldiers during a field operation. Often, the point man led the column of soldiers along a single path or dike. These were the likely places where booby traps, grenades, ‘bouncing Bettys’ and enemy soldiers might be first encountered.

[2] Military Occupational Service.

CONTRIBUTORS: Cathy Te Slaa, proof reader, Caesar Orosco, Web Master and proof reader, Tony Sparaco, Vietnam Veteran, Josephine Moore, Editor.

Reader comments:

Response to The Long Silence

Reading The Long Silence was, for me, like my brother was speaking to me from the grave. He was a U.S. Army Vietnam veteran and passed away on October 15, 2019 at the age of 75.

He was always a man of few words and even more so after coming back from Vietnam. He never talked about it except for one incident. That was when I asked him what he was doing on his birthday on Feb. 12, 1968. I had a dream that night that he was in a foxhole and I was with him. There was water in the bottom and my feet were very cold. There were rockets or gunfire or something “fire” overhead. That is all I remembered of the dream.

He looked surprised and said that is exactly what was happening on his birthday.

He had health issues after returning but would never see a doctor. He and his wife have one son who is now grown and has children of his own. But his wife had several miscarriages and they had one full term baby girl who was born with numerous deformities. She lived for 10 days. So he was haunted by Vietnam until he died but never spoke about it.

He is buried next to his baby daughter.

-Arlene S.

“Why should I remember what took many years to forget?” asked a Vietnam veteran.

For nearly thirty-five years, I rarely spoke about the Vietnam War with anyone. I found no compelling reason to talk about it. Exceptions to that silence were few—perhaps to answer a question from a friend or family member, or during an infrequent conversation about Vietnam with my wife. If I had to talk about it, more often than not, I would trivialize the experience. Bad times were really not that bad, or talking only about the good, the funny, or not-so-difficult times.

But there was no way I could control life events, and sometimes something happened that forced me to a recall an experience from Vietnam. These penetrations past my mental blockages came at surprising, unexpected moments, connecting me in some way to my time in the war—a hitchhiker trying to catch a ride on an approach to a highway, seeing a serviceman in uniform, or hearing the whoop-whoop of an Army helicopter overhead.

After returning from Vietnam, I wanted to move on with my life. My mind and my lips snapped shut on Vietnam. I had many reasons constricting my lips and closing my mind.

Most returning Vietnam veterans quickly learned that there was divided public opinion about the war. Even those veterans who were willing to talk about their experiences were reticent to breach the topic in conversation.

We were not welcomed as returning patriots or conquering heroes to America. A large segment of the population greeted us with silence, a deep distrust, and even disdain. As one Vietnam veteran put it, “The road home from war and the quiet that followed was sobering.” We were even shunned by veterans of prior wars. For many years after the war ended in 1975, the American Legion would not accept Vietnam veterans into their membership. They told us that Vietnam was never a real war and, by inference, we were not real soldiers.

Few people were interested in learning more or opening their perceptions of Vietnam. In that silence, my own recollections of Vietnam faded. It seemed easy to bury my recollections of the war into a vault to be forgotten and never opened again. My amnesia was self-inflicted.

But my silence around Vietnam was also self-preservation. It avoided questions like, “Did you ever kill anybody?” or “What was it like to shoot somebody?” “What was the worst thing that happened to you in Vietnam?”

I presumed that the people asking those questions had little interest in hearing the more important stories behind the headlines—the heartache of losing a brother to injury or death, the anger of obeying insane orders from a superior officer, the persistent feeling of loneliness and isolation. How does one explain the experience of living on an “island of war?”

To avoid the possibility of such conversations, I avoided the subject altogether. However, I’ve since learned from talking with fellow Vietnam veterans, that they too carried that same sort of reticence to relive their experiences. They—like me—were unsure whether they would be able to control themselves if those memories were awakened.

Perhaps there is a more truthful, personal answer to the question: Why was I so quiet about Vietnam for so long? Was I was afraid of awakening that sleeping monster along with its entourage of protégé monsters? Did I fear that retelling, rehashing, or rehearing about the Vietnam war would stir up emotions so overwhelming that I would not be able to control myself, and my emotions in turn would take control of me? I was paralyzed by the possibility that opening this Pandora’s box of the confusion and chaos of Vietnam would consume my existence.

I had no known physical wounds from Vietnam—unlike thousands of others who still suffer those consequences to this day. For them, there are daily conscious and subconscious reminders of Vietnam. The ever-present physical damage and emotional wounds left some brothers with thoughts of suicide. The scars incurred in Vietnam did not necessarily fade away.

I knew of other veterans whose lives had been so shattered by Vietnam that they had disintegrated into poorly functioning human beings. What if I would be no different? I had not yet been tested to know how I might react if I broke the long silence. I had consciously chosen to maintain my silence, that is, until my phone rang.

II. The Long Silence Lifts

The caller asked, “Is this the Norm Te Slaa who served with the 5th of the 60th Infantry Division of the 9th Division in Rach Kien, Vietnam?”

I fell silent for moment. After all these years, how could a voice suddenly emerge, seemingly out of nowhere, and ask about Vietnam? Was this a crank call or a sales pitch?

He sensed my reticence and quickly introduced himself. “Norm, this is Tony. We served together with the 5th of the 60th in Rach Kien.”

I quickly searched my dusty memories for his name. Yes, I remembered a Tony, but I barely knew him in Vietnam. That was not unusual, as we usually referred to each other by last names or some nickname the men had conjured up.

I vaguely recalled him. There was a day during my third month in the field when he had been walking point [1] and was injured by a booby trap. He was shipped back to the United States for hospitalization, recovery, and a purple heart. I had not heard from him or about him since then.

He continued, “Norm, have you heard that the 5th of the 60th has been having battalion reunions every other year for the last several years?” I hesitatingly answered that no, I had not heard about them. My conversation with Tony moved slowly, mainly because of my delayed responses to his comments and questions. I had a hard time understanding why he was calling to invite me to a reunion now. I was not prepared for such a call. In so many ways, it was the furthest thing from my mind.

Tony then invited me to attend the battalion reunion coming up in St. Louis in the spring of that year. As we talked, he told me more about the four previous reunions, and he mentioned that the special guest speaker at the next reunion would be one of the generals of our battalion during 1969, General Franks. His name also barely registered in my memory.

I was wary of attending and my doubts continued. After all, I could not remember many names from 1968 to 1969, only four or five came to mind, and these blank spaces in my memory concerned me. If I did attend, how could I even carry on a good conversation with the others? I was even unsure of my assigned platoon and squad number. And yet, my memory of certain events during that year could still be played back in technicolor.

Did I want to continue this conversation? If I did continue, would my confusion and feelings of chaos around my memories of Vietnam come crashing in, destroying my quiet life and successful career?

But slowly, I relaxed, and my reticence eased. I shifted from shielded to inquisitive, and I began to ask questions. The conversation began to feel more normal, even as my doubts about attending this reunion continued to bubble up.

My first impulse was to say no to the invitation. But hesitantly, I said I would think about it. I needed time to deliberate whether I wanted to let Vietnam back into my life. Sometime later, I called Tony back and told him, yes, I would come. But my doubts and apprehensions lingered.

Yet, I knew I needed to give my long silence a trial termination.

III. The Long Silence Ends

I attended my first reunion in the spring of 2012. Remembering Vietnam was initially very difficult; I could only recall a few names and places associated with Vietnam. But beginning with my first reunion, connections with my Vietnam past began to emerge.

I found myself among veterans who were not only willing to talk about Vietnam—they wanted to. We felt an immediate understanding and comradery among us. It was my first recollection of another Vietnam veteran calling me ‘brother’.

I soon learned that the 5th of the 60th reunion was an emotionally safe place. For many, the reunion was an act of self-preservation—finding a space where others understood them, also carrying similar questions, doubts, and apprehensions. At the reunion, veterans were ready to talk about Vietnam.

All around us were reminders of the physical damage. Some brothers lived every day with the tangible legacy of their Vietnam service. The manifestations of psychological damage, however, was less noticeable, at least initially.

I was relieved that others were also surprised at how little they recalled about details of daily existence in Vietnam. They, too, were hesitant to relive their experiences and had participated in their own ‘long silence.’ Fellow veterans said things like, “I don’t remember that.” or “What was his name?” or “Did we do that?”

I also learned that every Vietnam veteran had experienced a different version of Vietnam. Understanding these differences of experiences began with a soldier’s Military Occupational Service—their MOS. [2] I had been ground infantry, the MOS designation for which was 11B.

Approximately 2.7 million American men and women served in the Vietnam War, and for each 11B soldier in the field, it took eight or nine soldiers in the rear to support them. That breadth of different duties help account for the wide spectrum of interpretations of the Vietnam soldier’s experience.

Some of those 11B soldiers who had witnessed and participated in combat and bloodshed were left with emotional wounds. They returned home only to be swallowed up in their own quiet, psychological quagmire that filled their lives with trauma. And for the soldiers returning with lifelong physical damage, there was no escape from the daily reminder of their Vietnam service.

Few soldiers ever aired their emotional wounds. Some waited for years before allowing their Vietnam memories back into their thoughts. But some veterans seized the opportunity to unload their burdens at battalion reunions.

At a reunion of a battalion of grunts, among fellow, trusted brothers, veterans did not need to be as cautious as they talked about their memories and traumas. I saw this at my first battalion reunion. One brother’s expression of his trauma still replays vividly in my memory.

On the first day of my first reunion, Tony and I were walking down the hotel hallway, passing rooms with different gatherings of brothers, usually grouped by platoon. These gatherings were called ‘talk backs’ when brothers could meet with their squad or platoon and just talk about what was on their mind or reminisce together. Each room’s door was open, welcoming any latecomers.

We were talking as we passed by the third door when Tony suddenly grabbed my arm, stopping us. He shushed me and said, “Please be quiet! One of the guys is spilling his guts.”

Silently from the hallway we observed a brother sharing his trauma with his platoon. He was sobbing and in obvious distress. Neither of us heard what he was saying, but we could feel that it was an emotional avalanche. We were witnessing decades of emotional pressure being released.

For me, not being in the room, I feared we were betraying the confidence of our brother inside the room. After all, we were eavesdropping at a moment when he was finally able to bare his soul among his comrades and confidants, each of whom listened with understanding, compassion, and without judgement. Did I have the right to observe such a personal expression without his permission? The sight brought tears to my eyes. I could only imagine his sadness, his long-endured pain, and the endless sleepless nights he had suffered.

Tony and I moved on down the hallway, hoping the dark cloud enveloping this brother might now lift. To this day, when I think of him—and so many others—carrying such suffering, I find it hard to hold back my own tears.

This moment from my first reunion—and many more like it—is a testament to the fact that the emotional scars from Vietnam don’t necessarily melt away. The wounds of war can mark us indefinitely. These daily reminders of the Vietnam trauma—both conscious and subconscious—pick at the scabs of our memories.

At the age of twenty-three, I was one of the older grunts in my platoon. My maturity may have been one of the reasons why I sustained fewer traumas than some of my teenaged platoon brothers. The other reason being that my main field time job was as a radio operator, in addition to being a rifleman.

My main job was to carry the radio for the platoon leader, usually a second lieutenant. The two of us were usually in the middle of a line formation. My job was to have the field radio immediately available for the platoon leader so he could maintain contact with other platoons of the company or headquarters company.

Because of my radio responsibilities, I was also never tasked to carry an injured or deceased brother to a medivac helicopter. I never had to bind up the wounds of a booby trap or gunshot victim. That’s not to say I didn’t see them happen. I did. But for the most part, I was spared some of the severity of that trauma. Others who carried our brothers and bound their physical wounds, went on to carry their own emotional wounds throughout their lives. I am eternally grateful to my brothers, and especially our medics, who bore the responsibility of taking care of our injured and fallen soldiers.

Now, many years later, I still need to come to terms with certain subjects. A tear might unexpectedly appear when certain subjects come up. When that happens, my face freezes, my lips purse, and my mouth closes tightly, I swallow hard as I try to hold my emotions captive and avoid embarrassment.

After more than a decade of unpeeling the protective layers of silence, I began to see how close to the surface my own emotions actually are. I won’t go into detail here, but two very public events happened relatively recently that poked that slumbering monster within me. During each, I was asked to recall an experience, and doing so forced me to confront the fact that the pain of some events was still fresh within me.

I don’t regret what I did in Vietnam. I did as I was told. I also prayed a lot. I smoked packs of cigarettes every day, and I tried to stay close to my moral anchors. I did what I could to protect my brothers, and I took control of situations when I could to shield others from further harm. I am not ashamed of anything I did during my time in Vietnam. This alone helps me sleep peacefully.

So, why do I now write about something that happened so long ago?

First, I write because the remembrance of the Vietnam War is fast fading from the American conversation. Today, the people who might understand or even care about a living soldier’s story of his Vietnam War, and the people who walked those roads and rice paddies, manned and survived the ambushes, rode innumerable eagle flights, and walked miles and miles of search and destroy missions, are dying away. Soon, the Vietnam War will be only a footnote in history.

Second, I write because I cannot forget or ignore the sacrifices made by the 56,478 soldiers who gave their lives, and the over 300,000 soldiers physically injured—and even more emotionally wounded—in service of our nation’s call to duty. How can I remain silent in the face of their absent limbs, fractured minds, and muffled voices from the grave? Staying silent only increases the injustice of their sacrifice.

Third, I write to remind the public that there are people living among us who agreed to risk their lives for our country. Why should I not do what I can to honor their commitment to serve and face the danger of dying in war?

And finally, I write because many veterans have come to understand that none of us can keep our Vietnam combat experiences silent and locked away. If we ignore what happened in Vietnam, we do so at our own peril.

Until recently, I felt that wearing a Vietnam veteran cap was a distraction. But I no longer feel that way. Quite the opposite. Now, wearing this cap reminds me and others who see the cap’s insignia that there was such a momentous American event called the Vietnam War. It involved not only the people who served in the military. It touched and affected all of America. It tore our society apart.

Many Americans and Vietnamese died. Many more were injured. Some recovered from their injuries, but many did not. Wearing a reminder of the Vietnam War speaks to the sacrifices and the price that thousands of American soldiers paid, and continue to pay today. And we speak to break the long silence that holds us captive.

Why shouldn’t we remember what it took many years to forget?

Footnotes:

[1] A soldier walking point was the first in a line of soldiers during a field operation. Often, the point man led the column of soldiers along a single path or dike. These were the likely places where booby traps, grenades, ‘bouncing Bettys’ and enemy soldiers might be first encountered.

[2] Military Occupational Service.

CONTRIBUTORS: Cathy Te Slaa, proof reader, Caesar Orosco, Web Master and proof reader, Tony Sparaco, Vietnam Veteran, Josephine Moore, Editor.

Reader comments:

Response to The Long Silence

Reading The Long Silence was, for me, like my brother was speaking to me from the grave. He was a U.S. Army Vietnam veteran and passed away on October 15, 2019 at the age of 75.

He was always a man of few words and even more so after coming back from Vietnam. He never talked about it except for one incident. That was when I asked him what he was doing on his birthday on Feb. 12, 1968. I had a dream that night that he was in a foxhole and I was with him. There was water in the bottom and my feet were very cold. There were rockets or gunfire or something “fire” overhead. That is all I remembered of the dream.

He looked surprised and said that is exactly what was happening on his birthday.

He had health issues after returning but would never see a doctor. He and his wife have one son who is now grown and has children of his own. But his wife had several miscarriages and they had one full term baby girl who was born with numerous deformities. She lived for 10 days. So he was haunted by Vietnam until he died but never spoke about it.

He is buried next to his baby daughter.

-Arlene S.

4. Stop it! Stop it! Stop it!

One of the few missions that platoons and companies assigned to fight in the Vietnamese Delta looked forward to—if the grunts looked forward to anything—was providing additional firepower to the Mobile Riverine Force. A Navy concoction created for the unique demands of fighting in a waterlogged Mekong Delta, the Riverines patrolled all the waterways, large and small, of the Vietnam Delta.

Their boats were modest in size, about thirty feet long and twelve to fifteen feet wide, with lots of thick steel. They typically traveled in caravans of four or five boats. The Army offered additional security, firepower for the Riverines and the flexibility to pursue the enemy. The Navy in return provided the Army grunts with regular hot meals and clean bunks for a few days.

Together, they sought out the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army Regulars among the many rivers and tributaries of the Mekong Delta. If sightings or battalion intelligence spotted enemy activity, the Riverines and the Army grunts would engage the enemy from the boats. After the firing was over, the grunts would slog ashore through mud and water, try find and engage the enemy again, then return to the boats.

The Riverine boats bristled with firepower. The centerpiece of the firepower was a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on the bow of the boat. When attacked, the 50-caliber machine gun and the grunts riding “shotgun” were the first to engage the enemy.

As the Riverine boats patrolled the water conduits linked to the Ho Chi Minh trail that the enemy used for moving supplies from North Vietnam, the soldiers remained alert, always looking for suspect sampans carrying supplies deeper into the Delta. The VC and the NVA often transported weapons and supplies under the cover of darkness. If daylight came before the sampan cargo reached its destination, the enemy submerged the sampans in offshoots of a larger stream, with the muddy waters of the delta camouflaging the sunken sampans. Occasionally, patrols and the Riverines spotted them as the boats crossed streams, with the grunts looking carefully into the murky water.

Their boats were modest in size, about thirty feet long and twelve to fifteen feet wide, with lots of thick steel. They typically traveled in caravans of four or five boats. The Army offered additional security, firepower for the Riverines and the flexibility to pursue the enemy. The Navy in return provided the Army grunts with regular hot meals and clean bunks for a few days.

Together, they sought out the Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army Regulars among the many rivers and tributaries of the Mekong Delta. If sightings or battalion intelligence spotted enemy activity, the Riverines and the Army grunts would engage the enemy from the boats. After the firing was over, the grunts would slog ashore through mud and water, try find and engage the enemy again, then return to the boats.

The Riverine boats bristled with firepower. The centerpiece of the firepower was a 50-caliber machine gun mounted on the bow of the boat. When attacked, the 50-caliber machine gun and the grunts riding “shotgun” were the first to engage the enemy.

As the Riverine boats patrolled the water conduits linked to the Ho Chi Minh trail that the enemy used for moving supplies from North Vietnam, the soldiers remained alert, always looking for suspect sampans carrying supplies deeper into the Delta. The VC and the NVA often transported weapons and supplies under the cover of darkness. If daylight came before the sampan cargo reached its destination, the enemy submerged the sampans in offshoots of a larger stream, with the muddy waters of the delta camouflaging the sunken sampans. Occasionally, patrols and the Riverines spotted them as the boats crossed streams, with the grunts looking carefully into the murky water.

One day, the boats patrolled the Mekong River near the Ben Luc Bridge, a quarter-mile long bridge that served as the main thoroughfare between two South Vietnamese provinces. The Navy Riverine boats often guarded the middle of the bridge while both ends of the bridge were guarded by the Army, a light-duty assignment most grunts appreciated.

But there was also boredom on the Riverine missions. On this particular quiet afternoon, some grunts had stripped naked and had jumped from the moored gunboat into the river for a swim. Other soldiers had gathered about the 50-caliber machine gun and the platoon sergeant.

But there was also boredom on the Riverine missions. On this particular quiet afternoon, some grunts had stripped naked and had jumped from the moored gunboat into the river for a swim. Other soldiers had gathered about the 50-caliber machine gun and the platoon sergeant.

Then, without warning, the clatter of the machine gun cut through the calm, erupting with bursts of fire. Soldiers in the water frantically swam back to the boat believing the machine gun operator had spotted the enemy and had opened fired on them.

The startled grunts on the boat immediately reached for their weapons. A Specialist 4 in the back of the boat grabbed his M16. He looked at the platoon squad leader seated behind the 50-caliber machine gun and the small group gathered around it. The squad leader was behind the machine gun, his hand on the trigger, firing intermittent bursts of fifteen or twenty rounds each. The few soldiers around him were not alarmed and not acting as if they were under attack.

The platoon quickly realized there was no ambush. For amusement, the platoon sergeant was using the Ben Luc Bridge, which stood about a click [1] away, for target practice! About every fifth round was a tracer round, giving off visible streaks so everyone could see what was targeted.

The bridge bustled with many people on foot, some riding bikes and others driving motorized vehicles. Not one was a threat to the Riverines and the grunts. The only threat was the soldiers, endangering the civilians travelling across the bridge.

Horrified, the Specialist 4 shouted from the back of the gunboat, “STOP IT!” The E6 sergeant ignored the lesser-rank soldier. After another burst of fire, the Specialist 4 yelled louder to the platoon sergeant, “Stop It!”. After another burst of fire, the Specialist 4 shouted a third time “STOP IT!” and the E6 sergeant exploded. He jumped up and stormed to the back of the boat, fuming with rage that this lowly Specialist 4 would challenge his own platoon sergeant. The sergeant drew from his hip holster a long-barreled, 8mm pistol, raising it as he approached the Specialist 4.

Without flinching, the soldier stood his ground.

The sergeant thrust the pistol under the soldier’s jaw and into the softness of his throat. Addressing the Specialist 4 by name, he raged, “You mother fucker! I’m gonna blow your fuckin’ head off!” as he pushed the pistol harder into the Specialist 4’s throat.

“What are you doing, Sergeant?” the Specialist 4 asked. “They’re innocent civilians!”

Soldiers in the back of the boat contested the sergeant’s bad behavior and tried to calm him. After about twenty seconds—but seemed like minutes—he lowered his pistol and, fuming and cursing, walked back to the front of the boat.

The Specialist 4 stood surprised, saddened, angered, and shaken. The situation had been highly precarious. “How could such an event occur among fellow soldiers?” he thought. “We’re here to fight Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, not each other.”

He could only make sense of it because he already knew war could expose some of the darkest sides of our humanity. But most of the brothers in combat—thank goodness—held firm to their civility and never lost sight of our common humanity.

Footnotes:

[1] A ‘click’ was approximately a kilometer. It was used as a measurement of distance that could easily be heard over a radio transmission.

CONTRIBUTORS: Caesar Orosco, Web Master; Josie Moore, Editor

The startled grunts on the boat immediately reached for their weapons. A Specialist 4 in the back of the boat grabbed his M16. He looked at the platoon squad leader seated behind the 50-caliber machine gun and the small group gathered around it. The squad leader was behind the machine gun, his hand on the trigger, firing intermittent bursts of fifteen or twenty rounds each. The few soldiers around him were not alarmed and not acting as if they were under attack.

The platoon quickly realized there was no ambush. For amusement, the platoon sergeant was using the Ben Luc Bridge, which stood about a click [1] away, for target practice! About every fifth round was a tracer round, giving off visible streaks so everyone could see what was targeted.

The bridge bustled with many people on foot, some riding bikes and others driving motorized vehicles. Not one was a threat to the Riverines and the grunts. The only threat was the soldiers, endangering the civilians travelling across the bridge.

Horrified, the Specialist 4 shouted from the back of the gunboat, “STOP IT!” The E6 sergeant ignored the lesser-rank soldier. After another burst of fire, the Specialist 4 yelled louder to the platoon sergeant, “Stop It!”. After another burst of fire, the Specialist 4 shouted a third time “STOP IT!” and the E6 sergeant exploded. He jumped up and stormed to the back of the boat, fuming with rage that this lowly Specialist 4 would challenge his own platoon sergeant. The sergeant drew from his hip holster a long-barreled, 8mm pistol, raising it as he approached the Specialist 4.

Without flinching, the soldier stood his ground.

The sergeant thrust the pistol under the soldier’s jaw and into the softness of his throat. Addressing the Specialist 4 by name, he raged, “You mother fucker! I’m gonna blow your fuckin’ head off!” as he pushed the pistol harder into the Specialist 4’s throat.

“What are you doing, Sergeant?” the Specialist 4 asked. “They’re innocent civilians!”

Soldiers in the back of the boat contested the sergeant’s bad behavior and tried to calm him. After about twenty seconds—but seemed like minutes—he lowered his pistol and, fuming and cursing, walked back to the front of the boat.

The Specialist 4 stood surprised, saddened, angered, and shaken. The situation had been highly precarious. “How could such an event occur among fellow soldiers?” he thought. “We’re here to fight Viet Cong and the North Vietnamese Army, not each other.”

He could only make sense of it because he already knew war could expose some of the darkest sides of our humanity. But most of the brothers in combat—thank goodness—held firm to their civility and never lost sight of our common humanity.

Footnotes:

[1] A ‘click’ was approximately a kilometer. It was used as a measurement of distance that could easily be heard over a radio transmission.

CONTRIBUTORS: Caesar Orosco, Web Master; Josie Moore, Editor

1. 2nd platoon ready for a swim 2. Mobile Riverines on patrol

3. Squeak

INTRO TO SQUEAK: The subject of this story happened occasionally while on field missions. This one was for me, also affirmed by another brother, as one of such events that stands out among others like it. Hope you enjoy the story.

It was a normal ‘search and destroy’ mission that began sometime during the Vietnamese dry season.[1] Charlie Company, of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Infantry, was preparing for a field operation that would be a considerable distance from the Rach Kien base camp. Staff Sergeant Kay told the men to pack all the ammunition they could carry. This more-distant-than-normal mission might last three or more days. Although food and ammunition were usually resupplied to the field troops by helicopter, it didn’t always happen.

The troops in Charlie Company gathered for the five UH-1 helicopters that would pick them up on the gravel road outside of the firebase. Once they were in the air, the ride to the target area took about fifteen minutes, landing the platoon in a cold LZ[2].

For the next two days, they made no daytime or nighttime enemy contact. Near the end of the second day of the mission, the platoon was getting low on food and water. The GIs realized that the helicopter would not be returning to supply them with canned food and water, since no enemy contact was reported to battalion headquarters, and the ammunition of Charlie Company was still in full supply.

With food and water diminishing and hunger and thirst mounting, the grunts had few alternatives. It was not the first time they would need to scavenge for food and water, and their only choice was to seek sustenance from the local Vietnamese villagers.

By late afternoon of the second day, the men began walking to a nearby village. There were seven or eight hooches in a nearby village where local mama-sans were preparing a butchered chicken or duck that surrounded their hooches. Because each hooch could accommodate, at most, five or six people, the platoon broke up into squads and approached different hooches, asking for food.

A squad leader approached the opening to a hooch that contained a mama-san and two small children inside: there was no papa-san in sight. The squad leader poked his head inside, noticed a large black pot over and open fire and blurted out the only Vietnamese words he knew: “Hey, Mama-san! Chop-chop?” as he circled his hand over his belly and, gestured with imaginary chop sticks, scooping food into his mouth.

A squad member reached around the squad leader, addressing the congenial mama-san with the same question: “Mama-san, chop-chop?” he said as he circled his hand over his belly and, with the other hand, motioned as if scooping food into his mouth. Mama-san immediately knew what they were asking. Perhaps, she had previously met other GIs with similar requests and motions.

With a friendly smile and a welcoming gesture, she invited the six hungry soldiers into her doorless hooch. The dirt floor was hard, worn smooth and almost shiny by family traffic and sweeping; a straw broom leaned against a nearby wall. The mama-san was making the evening meal for herself and her children. Whiffs of rice and meat cooking mingled with the pungent smell of the burning rice straw and nippa palm wood under the pot, smells the GIs had encountered many times before.

The soldiers sat down in a half-circle with their legs crossed and facing the large black pot. The mama-san set about adjusting her ingredients to accommodate what would now include six unexpected, hungry soldiers.

Within minutes the mama-san passed out earthenware bowls and chop sticks to each of the soldiers. She went around the room spooning a large portion of rice on each of the plates held out by outstretched American hands. Etiquette and good manners took a back seat to hunger as the GIs began to eat the moment their bowls were filled with rice.

The mama-san returned to the black pot, and with the kettle in one hand and a ladle in the other, she went around the hooch, giving her surprise guests a small portion of perfectly cooked meat and juice on top of their remaining rice.

The soldiers expressed their gratitude to the mama-san. They knew what it meant that the mama-san was willing to share a meal of such value with total strangers. The free-range chickens and ducks from her yard, and the fish from a nearby rice paddy or delta stream, were valuable to her and her family.

She smiled at the Americans’ enthusiasm as they ate her Vietnamese food. The hungry soldiers muttered their approvals with complimentary grunts of “hmm” and “Hey, that’s good” as they eagerly gulped down the cooked meat and beautifully cooked rice on their plates. The mama-san seemed to have added some spices to the otherwise bland meat and rice.

The meat was especially tasty. The pieces were of different sizes and shapes, all mostly small. They were light in color, tasting and looking like chicken bits but with a slight tinge of yellow. The texture was also different - it was a uniform texture but had granule-like sparkles as though the meat had crystalized.

The radioman addressed the mama-san between bites of food: “Mama-san, number-one chop-chop!” as he rubbed his stomach and motioned with his chopsticks to the food on his plate. Others chimed in or nodded their agreement. He asked mama-san a question: “Mama-san, Chicken? Duck"?

She looked puzzled as the GI asked his question. It was obvious she did not understand. The GI asked a more specific question: “Mama-san, number-one, chop-chop. Chicken? Duck?” He pointed to the chickens and ducks outside of the hooch and then the meat on his plate.

Now she understood what he was asking!

A smile quickly crossed her face, and she threw her head back with a little laugh. She responded with another Vietnamese word that none of the GIs could understand. She looked at the puzzled GIs as if to say, Why don't they understand?

Finally, she stood up from her haunches and moved to the edge of the hooch.

With her knees bent and leaning forward, she reached out to the edge of the hooch, put her hand at the very bottom of the wall, and used her two fingers in imitation of a fast-running figure. She took small steps while her two fingers acted out a fast, imaginary walk along the bottom edge of the hooch, repeatedly saying in a high-pitched voice “Squeak, squeak.” “Squeak, squeak.” “Squeak, squeak.”

She then turned and smiled at the soldiers sitting on her floor, confident they would now understand about the meat on their plates.

Her “dinner party” guests looked at each other, then looked down at what remained of their meal of meat and rice.

They were silent. They looked back at each other in disbelief!

They had just eaten their first boiled rat!

Footnotes:

[1] Dry season was from November to April

[2] A cold LZ was a landing zone without incoming enemy fire.

Contributors: Cathy Te Slaa, proofreader, Josephine Moore, Editor

Reader comments:

"We must have been in different hootches. Mine was chicken and rice and we all chipped in two dollars worth of P each." -Bob L.

It was a normal ‘search and destroy’ mission that began sometime during the Vietnamese dry season.[1] Charlie Company, of the 5th Battalion of the 60th Infantry, was preparing for a field operation that would be a considerable distance from the Rach Kien base camp. Staff Sergeant Kay told the men to pack all the ammunition they could carry. This more-distant-than-normal mission might last three or more days. Although food and ammunition were usually resupplied to the field troops by helicopter, it didn’t always happen.

The troops in Charlie Company gathered for the five UH-1 helicopters that would pick them up on the gravel road outside of the firebase. Once they were in the air, the ride to the target area took about fifteen minutes, landing the platoon in a cold LZ[2].

For the next two days, they made no daytime or nighttime enemy contact. Near the end of the second day of the mission, the platoon was getting low on food and water. The GIs realized that the helicopter would not be returning to supply them with canned food and water, since no enemy contact was reported to battalion headquarters, and the ammunition of Charlie Company was still in full supply.

With food and water diminishing and hunger and thirst mounting, the grunts had few alternatives. It was not the first time they would need to scavenge for food and water, and their only choice was to seek sustenance from the local Vietnamese villagers.

By late afternoon of the second day, the men began walking to a nearby village. There were seven or eight hooches in a nearby village where local mama-sans were preparing a butchered chicken or duck that surrounded their hooches. Because each hooch could accommodate, at most, five or six people, the platoon broke up into squads and approached different hooches, asking for food.

A squad leader approached the opening to a hooch that contained a mama-san and two small children inside: there was no papa-san in sight. The squad leader poked his head inside, noticed a large black pot over and open fire and blurted out the only Vietnamese words he knew: “Hey, Mama-san! Chop-chop?” as he circled his hand over his belly and, gestured with imaginary chop sticks, scooping food into his mouth.

A squad member reached around the squad leader, addressing the congenial mama-san with the same question: “Mama-san, chop-chop?” he said as he circled his hand over his belly and, with the other hand, motioned as if scooping food into his mouth. Mama-san immediately knew what they were asking. Perhaps, she had previously met other GIs with similar requests and motions.

With a friendly smile and a welcoming gesture, she invited the six hungry soldiers into her doorless hooch. The dirt floor was hard, worn smooth and almost shiny by family traffic and sweeping; a straw broom leaned against a nearby wall. The mama-san was making the evening meal for herself and her children. Whiffs of rice and meat cooking mingled with the pungent smell of the burning rice straw and nippa palm wood under the pot, smells the GIs had encountered many times before.

The soldiers sat down in a half-circle with their legs crossed and facing the large black pot. The mama-san set about adjusting her ingredients to accommodate what would now include six unexpected, hungry soldiers.

Within minutes the mama-san passed out earthenware bowls and chop sticks to each of the soldiers. She went around the room spooning a large portion of rice on each of the plates held out by outstretched American hands. Etiquette and good manners took a back seat to hunger as the GIs began to eat the moment their bowls were filled with rice.

The mama-san returned to the black pot, and with the kettle in one hand and a ladle in the other, she went around the hooch, giving her surprise guests a small portion of perfectly cooked meat and juice on top of their remaining rice.

The soldiers expressed their gratitude to the mama-san. They knew what it meant that the mama-san was willing to share a meal of such value with total strangers. The free-range chickens and ducks from her yard, and the fish from a nearby rice paddy or delta stream, were valuable to her and her family.

She smiled at the Americans’ enthusiasm as they ate her Vietnamese food. The hungry soldiers muttered their approvals with complimentary grunts of “hmm” and “Hey, that’s good” as they eagerly gulped down the cooked meat and beautifully cooked rice on their plates. The mama-san seemed to have added some spices to the otherwise bland meat and rice.

The meat was especially tasty. The pieces were of different sizes and shapes, all mostly small. They were light in color, tasting and looking like chicken bits but with a slight tinge of yellow. The texture was also different - it was a uniform texture but had granule-like sparkles as though the meat had crystalized.